- Home

- Julie Berry

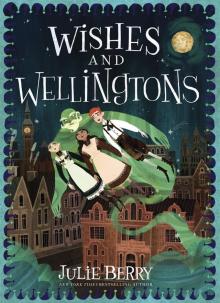

Wishes and Wellingtons Page 2

Wishes and Wellingtons Read online

Page 2

“Britannia…” he echoed softly.

“Our king, if you must know, is Queen Victoria, thank you very much, and the year is eighteen ninety-six.”

His eyes bulged. “Eighteen ninety-six? Is this, how do they call it, anno Domini?”

I nodded. “Time flies, eh?” Imagine, not knowing the year!

“That’s three hundred years I’ve been dormant,” he moaned. “Nobody’s found… Wait. Did you say your empire is ruled by a queen?”

“God save her,” I replied. “Ever since she was eighteen years old.”

“A woman?” He pressed the heels of his green hands into his forehead. “A young woman. By heaven, it’s no wonder girls are impudent nowadays. What kind of a world is this?”

One much more to my liking than whatever world he’d come from, that was plain!

But, back to business. If he thought he could put me off the scent of my prize, then he didn’t know Maeve Merritt.

“Come,” I said. “Admit it. You are a djinni. You are so a djinni. I’ve read about them. You must grant three wishes to whoever finds you. And I found you! So you belong to me. Those are the rules.”

Mermeros darted close to me until his giant face was inches from mine. “Then make a wish, Girl Hatchling,” he said softly. “Make one right now. The best you can think of.”

He hovered right over me, watching me closely.

A wish right now? Why not? Why wait? Then again, shouldn’t I think about it first?

“Go on,” he said. “Ask me anything. You’re not afraid, are you? You’re not such a weak-brained girl hatchling that you can’t even think of one tiny, pathetic wish?”

If Mermeros were a Luton boy from back home, or one of those orphan boys across the alley, he’d have an aching jaw right now, and I’d have an aching fist. But socking my djinni probably wasn’t the best way to begin our friendship.

I stroked my chin and walked slowly around him, pretending to think of a wish but in reality studying my prize.

He wore a vest of shimmering fish scales, and an embroidered skirt pinned like a kilt around his waist. Over it, like a belt, he’d tied a yellow silk sash. A thick silver hoop dangled from one ear, and—I couldn’t be certain, but I’d almost swear—an enormous shark’s tooth on a leather lace dangled at his throat.

“You can’t do it, can you?” He folded his great arms across his chest and smirked at me. “You lack the stomach to command me.”

The teeth behind his full turquoise lips were sharply pointed, like a fish’s.

“How do I even know it’s worth the bother?” I said. “How do I know you actually have the power to grant wishes?”

He bared his sharp teeth, then snapped his fingers. Immediately beside him stood a sinewy tiger, half as long as the alleyway, and ready to pounce. Mermeros studied my face and frowned. He snapped again, and the tiger vanished. Now a cobra coiled beside him, its hooded head darting back and forth seductively. Fascinating! But Mermeros’s eyes shot daggers of annoyance at my lack of fear. One more snap, and the cobra became a gigantic wild boar, its spiky back hair quivering, its red eyes burning.

I’d never been so close to a bloodthirsty monster, unless you counted my sister Evangeline before she’d had her breakfast tea.

“Brilliant,” I said. “Can you conjure up a bear?”

Mermeros’s green face turned a livid shade of purple. “Your wits are lacking, female. Strong men tremble at the sight of my menagerie.”

“How about an octopus?”

Just then, Mrs. Gruboil rattled her shutters once more, then poked her nose out of the window. My heart stopped. If she or anyone at Miss Salamanca’s School saw my green giant, they’d snatch him for themselves. He was mine, I’d dug in the trash all day and found him, and I was not about to let him slip through my grasp.

But Mrs. Gruboil never looked from left to right. A half-naked hovering green bald man out of the corner of her eye wasn’t worth turning to investigate. That is the problem with adults. They won’t bother to see what ought not to be there.

Mrs. Gruboil sniffed the air and scowled. “You’ve kicked up a stink, Miss Maeve. Hurry up, I said, and get those cans put away so you can wash!” She shut the window once more.

Mermeros looked affronted not to have been noticed, the peacock.

“You’d better get back into that sardine tin,” I told him. “We can talk more later.”

“I will not.” He stretched his huge arms. They were banded with tattooed rings in darker shades of blue and green. “I have no wish for further conversation with you.”

I crawled underneath him and snatched the sardine tin, then cranked the key backward to unfurl the tin covering. A sardine can, once opened, could never be shut again, but perhaps, I gambled, this one was different.

And right I was. It sealed shut, pulling Mermeros inside.

“Desist!” He billowed larger, looming over me so his fish-green eyes glared down into mine. His fists clenched, his muscles bulged with menace. “I warn you, female hatchling, not to incur my wrath. A thousand lifetimes are not enough to make Mermeros forget…”

But the cord of smoke was tugging him down into the tin, like the winding of a sailor’s rope on a spool. His green body turned back into thick yellow fumes once more and was sucked into the sardine tin, which sealed itself shut with the key back in place on the bottom, good as new.

I slipped him into my pocket and ran inside.

Chapter 3

“Don’t look now, girls. Maeve the Knave has come back inside for her bread and water.”

I stalked by Theresa Treazleton in a perfect imitation, if I do say so, of the way she usually pranced around. Nose held high. Wouldn’t she pop her eyeballs from her sockets if she knew what I had in my pocket?

Supper was over, and the rest of the girls were assembled in the sitting room on the third floor of the school, in the common hall outside the dormitory rooms for the seventh form. I’d already bolted my meal standing next to the sink in Mrs. Gruboil’s kitchen. A potato without butter, and a lukewarm chicken wing, just to remind me of my inferior punished status. I could smell from the dining hall the piping-hot chickens with potatoes, and gravy and hot apple crumble. But, no matter. My mind was too full of my astonishing discovery to dwell upon food. A djinni! Here, in London, and in 1896 of all things! Here we sat on the very verge of the twentieth century, and there I was, finding djinnis. It was just like in the book One Thousand and One Nights. How many times had I read Polly’s gilt-edged copy and envied the boy Aladdin!

After washing up, I headed up the stairs and encountered Theresa holding court in the sitting room, thronged by her minions. Theresa’s father ran a large shipping enterprise that made him rich as a lord, thereby guaranteeing his daughter would be the nastiest and most sought-after girl at any boarding school in Britain, except for the schools where daughters of real lords were sent.

Theresa’s black eye had gone from being truly blackish-purple to just purple, with a tinge of yellow at the edges. She reminded me of the pansies on Miss Salamanca’s office wallpaper.

“Maeve Merritt,” Theresa purred. “You poor thing. Having to muck about in the refuse for two days! And all because you were never taught to behave as a young lady should.”

She simpered at me. Her minions did the same.

“Kind of you to pity me, Theresa dear,” I said. “I should pity you, Miss Purple-Face.”

Theresa shot up out of her chair.

“You take that back!”

“Shan’t.”

Her fingers curled into a fist. “I ought to give you a black eye,” she said.

I thrust out my chin so she’d have an easy shot at me.

“Go ahead. I’ll hold still for you.”

I knew she’d never dare. Theresa fumed till spittle shone on her lower lip. She looked at her fist as though

it had already been injured on my skull, then released it. “You’re ugly, anyway,” she said. “Look at yourself. Filthy as a chimney sweep.”

“Filthier,” chimed in Honoria Brisbane, Theresa Treazleton’s chief minion, with the pert little face of a weasel. “Chimney sweeps don’t smell like barnyards.”

“Have you sniffed a chimney sweep lately, Honoria?” I said. “The company you keep! Well, good night. I’m off to take my bath and get to bed. Don’t strain your tongues gossiping.”

I strolled out of the sitting room and down the corridor to my bedroom. I knew I’d been sassier with them than I ought to be, and I was only asking for retaliation, which would in all likelihood occur during my bath, but carrying an almighty djinni in my pocket made me bold. So what if Theresa and Honoria and the others stole all my stockings and petticoats? My djinni could conjure up clothes fit for a queen or, better yet, clothes fit for a boy heading off to exploring the jungle. Oh! Now there was an idea. I should wear trousers! What a scandal. But when I considered that three wishes were all I’d get from Mermeros, I decided I didn’t want to waste one on useless clothing. So I stuffed a valise full of all my necessaries, just in case Theresa and Honoria had evil plans, and brought it with me into the bathroom, which I could lock from within while I took my soak.

The bath did wonders, and I was feeling much better when I lugged my valise, sardine can and all, back to my bedroom and prepared to climb between my sheets. I wore a fresh, clean nightdress, and my skin had that lovely tight, clean, soapy feeling that meant I’d scrubbed off every speck of dust and rubbish from the trash heaps.

I pulled back the bedspread and gasped. There, tucked between the sheets, was a note scrawled in large letters. “I know about your green man,” it said.

Chapter 4

“It’s awfully chilly in here, Maeve,” said a voice behind me. “What did you open the window for?”

I was too distracted by the note to pay attention to Alice at first. Alice Bromley shared my room with me at Miss Salamanca’s school, and she was a brick, really, once I got to know her. When I first met her, I thought she’d be the pretty, silly sort who wouldn’t dare muss her hands nor scuff her shoes. That was wrong of me. Alice is sensible, if a bit timid. True, she’s much too anxious about rules. But she’s as kind as Christmas, and loyal as anything. There’s none of that silly goggling around after Theresa Treazleton that most of the girls did all day. She has no use for Theresa, nor for the school. She pines for home and her beloved grandparents. Can’t blame her for that. Before this day’s find, I would have said having Alice as a roommate was the only good thing to happen to me at this school.

“What’s that you’re reading?” Alice peered over my shoulder. “What ghastly writing. And what’s that saying about a green man?” She giggled. “Do you have a green man, Maeve?”

I let the note fall back on the bed. Alice wouldn’t betray me, I thought. But would she believe me?

A chill breeze from the window blew over my wet hair and made me shiver. I crossed the room and closed the window. “I didn’t open the window. It must be that the maid… Oh!”

Down below, across the alley, in the back garden of the charitable home, I saw the red-haired orphan boy by the light spilling from their kitchen windows. He was watching my window. He ducked out of sight behind the woodshed, but even in the dim light there was no mistaking his orange hair, sticking out from under his cap. I waited.

“What is it?” Alice joined me and peered outside. “I don’t see anything.”

The orphan boy poked his head out slowly, then darted back out of sight once he saw me watching.

So. He was the spy who threatened to upset my secret prize! We’d see about that.

“There’s a boy down there!” Alice gave me a little shove. “Don’t stand in front of the window in your nightdress, you goose!” She sank onto her bed and began unlacing her boots. “You’re quite a mystery tonight. Did you think you saw a burglar?”

“No burglar,” I said. “But it was that boy who climbed in here and left this note.” I pulled the curtains firmly shut, then folded the incriminating slip of paper and stuffed it in my emergency valise. Young Master Redhead may have seen my green man once, but I’d make sure he never did again.

“Then he must be mad.” Alice wrenched off a boot. “The poor orphans, driven to insanity through the despair of loneliness and grief…”

“Oh, pooh,” I said. “You’re a kind soul, but those ‘poor orphans’ are just as rascally as any other boys. Back home, the boys in the village and I used to…”

“Your life back home always sounds so wonderfully savage.” Alice sighed and attacked the buttons on the high collar of her dress. “I wouldn’t dare have half the adventures you do. What would Grandmother say?”

“Your grandmother can’t say anything about what she doesn’t know.” I shoved my valise under my bed and slipped the precious sardine can into the pocket of my dressing gown, hanging near my bed. I’d have to come up with a better hiding place for it, but, for now, I wanted to keep it close.

“I miss Grandmother.” Alice looked wistful, then she brightened. “Speaking of notes, you received a letter from home today.” She pulled an envelope from her pinafore pocket and handed it to me.

It was from my eldest and best-beloved sister, Polydora. The only one of my three sisters whose brain wasn’t positively pickled by too many fashion magazines. Tall, thin, with spectacles and without marriage prospects, Polly was the only one back home who wrote regularly. Mother—hah!—barely wrote at all. I slit the envelope open and scanned the first lines.

“Dearest Maeve,” it read in Polly’s smooth, regular handwriting. “How I laughed when I read your last note! But you mustn’t be so glib about your teachers. It borders on disrespect, and it will interfere with your learning. Mother and Father send their love”—I wondered if they actually had, or if Polly was just being sweet as usual—“as do Deborah and Evangeline.” Now I knew Polly was fibbing. “We’re all eager for your Christmas visit.” Hmph. Not all, I’d wager. Mother was probably breaking out in hives at the thought of me coming home. “All is hubbub here since Evangeline’s engagement was announced, and there is a never-ending stream of tradesmen ringing our bell to show us silks and laces and stationery and candied almonds for the party. Mother is in her element, though Father worries constantly about the cost…”

I stuffed the letter in the pocket of my dressing gown, to save it for later. I always loved hearing from dear old Polly, but she would ramble on, and I had too much on my mind just now to be bothered with the cost of Evangeline’s bridal veil. I’d be glad of a diversion during tomorrow’s French class. I’d read the letter then.

I crawled under the covers and lay there thinking of my djinni and all the wishes I might choose. The diamond mines of Borneo! The silver mines of Peru! Not that I wanted wealth above other things, though I was no fool where money was concerned. With sacks of silver and diamonds and gold, they couldn’t very well order me into itchy, gray serge dresses anymore, nor make me conjugate my French verbs so I could someday find an ideal husband. (Perhaps I was intended to marry a Frenchman?) My mother had sent me to Miss Salamanca’s school to make a young lady out of me, so that in a few years’ time—very few, judging from Evangeline—she could marry me off. It was the one and only respectable way to dispose of a daughter. Unlike the good old days, before dear old Henry VIII, when parents could farm daughters off to abbeys to become nuns.

I wanted a different life. Independence. Travel. Sports. And all those things cost money. But with a djinni in my pocket—literally—who could stop me? I could travel the world, like Miss Isabella Bird. I could buy a great country house, turn the back gardens into my own private cricket lawn, and invite the best players in the country to play. But they’d have to let me bowl. And wear my own cricket flannels and cap. Oh! I’d start a cricket team for girls and teach them how t

o play. A whole league! I’d spread girls’ cricketing across the British Isles!

Maeve Merritt. Girl Traveler and Female Cricketing Champion of the World.

I lay there, heart thumping, imagining, and finally I decided I could wait no more to let Alice in on the secret. A secret this fantastically huge and stupendously amazing just couldn’t be kept by one person alone, or she might explode. Besides, I would want to know, if I were in Alice’s shoes. Wild horses wouldn’t drag her secret out of me. Friends are friends.

I sat up underneath the covers.

Alice had loosened her butter-colored hair and was now braiding it for bed.

“Alice,” I said. “Can you keep a secret?”

Her eyebrows rose. She hurried to my bed and sat by my feet. “Absolutely,” she whispered. “Is it something about the orphan boy?”

I wrinkled my nose in disgust. “No! This is a mysterious and fantastical secret. You’ll find it hard to believe. And you mustn’t breathe it to a living soul.”

Alice inched closer. “I swear it on my mother’s grave,” she said. “They can torture me with hot brands, but I’ll never…”

“Fine, fine.” Hot brands! Of all things! I pulled the sardine can from my dressing gown.

“That’s your secret?” Alice’s disappointment was plain. “A can of fish? I prefer kippers over sardines, myself.”

“No, silly,” I said. “This is no ordinary can of fish.” I lowered my voice even further. “There’s a djinni inside.”

Alice pursed her lips and gave me a long, slow look. “You’re not joking with me again, are you, Maeve?” she said. “This isn’t a prank?”

I shook my head. “On my honor, it isn’t,” I whispered. “I’d show you here, but then we’d be found out. I discovered him in the dustbin today, during my punishment. He conjured up a tiger and a cobra before my eyes, right out there in the alley! He came right out of this tin, sure as sugar.”

“But I thought djinnis lived in lamps,” Alice protested. “What’s he doing in a sardine can? And how did such a sardine can come to be here, in London, in Miss Salamanca’s School’s dustbins?”

The Amaranth Enchantment

The Amaranth Enchantment Secondhand Charm

Secondhand Charm All the Truth That's in Me

All the Truth That's in Me Lovely War

Lovely War The Emperor's Ostrich

The Emperor's Ostrich The Passion of Dolssa

The Passion of Dolssa Wishes and Wellingtons

Wishes and Wellingtons The Scandalous Sisterhood of Prickwillow Place

The Scandalous Sisterhood of Prickwillow Place Amaranth Enchantment

Amaranth Enchantment